GOSH - A history (⚙️ in the making…)

by @cassandreces - February 2020- EN |

- ES |

- FR

Notes:

- Hover over highlighted text to show comments

- Timeline keeps growing, come back for updates!

🔥 Welcome!

We are about to tell a story of people creating tools with other people. About knowledge(s), curiosity, questioning and sharing ideas, nurtured by the stories of those who are part of this collective. Its full name is Global Open Science Hardware movement, but since it is very long we affectionately call it GOSH.

Those of us who identify with GOSH values are a diverse group of people using different kinds of tools to produce knowledge. Whether within universities or schools, working in civil associations, ateliers or in our communities, we think that different and necessary things happen when the designs of the tools that produce knowledge are freely shared. To learn more about this you can check our manifesto and the article Why gosh?.

After four years of getting to know each other and a lot of work together, and after setting as our goal that open science hardware is ubiquitous by 2025, we understand it is a good moment to reflect on how we got here.

❝❞

I'm pretty sure in 20 to 50 years there's not going to be any research or any new technology that is not based at least partially on open hardware. Science needs to change and is going to change.

Tracing threads

Prior to 2016, before GOSH existed as a name or set of values in a manifesto, different people around the world were creating their own scientific tools and sharing their designs.

Some of them were teachers, building low-cost tools for their students to learn in more engaging ways. Others worked in laboratories and had started customizing and tweaking tools to make them useful for their new experiments, or to be able to do more with less resources. In some cases, people working with communities were putting together very low-cost hardware and software to run grassroots environmental monitoring efforts. Artists were already experimenting with these new platforms, in the interstitial space between art and science.

❝❞

Between 2010 and 2015 there was a lot of movement that started happening in Open Science and hardware, it kind of felt like you throw a firecracker and the sparklers go all over the place.

In most cases they combined 3D printing and open platforms such as Arduino or similar ones, and produced data, images, new ways of learning. Some names that were heard at the time referred to 'open labware' or 'diy science equipment'.

At that time other communities, such as the Open Hardware Association (OSHWA), were already gathering people working on open hardware but not particularly in science. Even a first GOSH already existed, although it referred to the Grounding Open Source Hardware (GOSH) initiative who met in 2009 to promote the certification and registration of projects, and was finally abandoned.

Part of this story takes us to 2014 when Jenny Molloy (University of Cambridge), Greg Austic (OurSci.net), Adam Wolf (who would later step back from the project due to other commitments) and François Gray (Citizen Cyberlab, Geneva-Tsinghua Initiative) met at the Mozilla Festival in London, UK. It was on this occasion that the idea of organizing a first event on open scientific hardware began to take shape, converging from different places.

Jenny and Greg had met almost by chance in the US, attending an open science event that had little to say about hardware. Jenny had been struck by the ideas she had heard in a previous event from Rafael Pezzi (Centro de Tecnologia Academica - UFRGS), about how they used open scientific hardware within university. Greg had a history of community science involvement in the US and was actively developing PhotosynQ.

François, who was involved in the Lego2Nano initiative to build an OpenAFM with students, had also been discussing the need of gathering people working on open science hardware with Shannon Dosemagen (PublicLab), who joined the organizers' group. Shannon was working since the beginning of the decade using open hardware with communities doing environmental monitoring in the US, and had witnessed the growth of the movement first-hand.Several emails and calls later, the group already had a better picture of what GOSH was going to be, and how it was going to happen.

Emerging

In 2015 preparations were under way for GOSH first gathering in 2016 at CERN Idea Square. Being in Switzerland, in October François contacted Marc Dusseiller (Hackteria) and Urs Gaudenz (GaudiLabs, Hackteria), who from different angles were already working with open science hardware since 2010. Besides co-founding Hackteria, Marc had been using open hardware in his science classes and the media-arts scene; Urs had developed an open set of tools for biology and was actively working on open hardware projects at his lab.

Although some last-minute logistical problems almost threatened the gathering, it was a success, convening an active group interested in working together.

Special mention: although he wasn't sure about it, emails confirm François was the one to come up with the name "GOSH" in 2015 (among other suggestions such as 'OH Science!').

A total of 54 people came together that March, mainly from Europe and the US: educators, scientists, entrepreneurs, community organizers. The four days of the program included keynotes by Sean Bonner (SafeCast project), Denisa Kera (philosopher and designer), Kickstarter crowdfunding experts, unconference sessions, workshops and presentations by local artists convened by Marc Dusseiller plus artists from the program Arts@CERN.

Most participants highlight how the spirit of the meeting was closer to a group retreat than to a typical conference: people cooking together, sharing spaces, building community. After three days of talks, workshops and discussion, the participants articulated the values of the community in the GOSH manifesto, which would lay the foundations for the work of the coming years. Max Liboiron and Greg Austic stewarded the first draft, which was later commented and signed by the participants, plus online collaborators worldwide through the website (such as Thomas Mboa, future co-founder of AfricaOSH).

It was January 2017 when Rafael inaugurated the GOSH forum, the virtual meeting point of the community, with a welcome post for everyone to introduce themselves, in particular those attending next year’s gathering.

❝❞

In academic conferences you have people that come talk for hours and then the most interesting discussions happen in the hallways. GOSH takes this whole thing and puts it the other way round, the ones in the hallways are brought to the middle, and not top down.

Aurora Thornhill (Kickstarter), Francois Grey (University of Geneva and CERN), Greg Austic (Michigan State University), Jenny Molloy (University of Cambridge), Marc Dusseiller (Hackteria), Shannon Dosemagen (Public Lab), Urs Gaudenz (Gaudi Labs)

Going global

After the first meeting it was clear that there was a strong community interested in open hardware for science. It also brought up that often people felt isolated, in need of support to promote open science hardware at their workplaces and communities.

❝❞

We are going to bring the question “What is open science hardware to you?” to different cultural locations in the world, and let that question be answered in whatever way it is answered in that place.

Thanks to the support of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and contributions from Mozilla Foundation and HardwareX, in March 2017 GOSH moved to Chile to understand how open science hardware was happening in other latitudes. The focus was made on strategies to build community and advance the field globally.

A hundred participants from 30 countries were selected under strict demographic criteria, based on the concept of equity for building the community. The code of conduct was put in place and people were designated to implement it during the event.

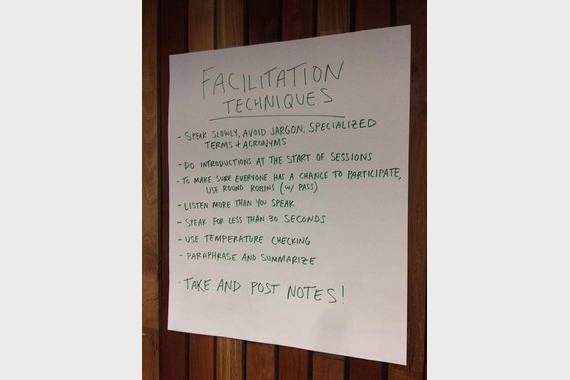

The program included four days of activity that began with facilitation techniques training for all participants, followed by short presentations and debate (replacing keynotes), unconference sessions and workshops, and a science fair including posters and projects, open to all public. After the four official days, some GOSHers continued to work collaboratively two more days to advance specific projects. All documentation of the event, self-managed by a volunteer team, was published online in the community forum.

The 2017 event also featured the launch of the Journal of Open Hardware, an international journal for publication of open access, peer-reviewed academic articles, managed by the community.

Fernán Federici Noe (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile), Francois Grey (University of Geneva and CERN), Greg Austic (PhotosynQ), Jenny Molloy (University of Cambridge), Max Liboiron (Memorial University of Newfoundland), Shannon Dosemagen (Public Lab)

Defining strategy

Once the community values were made explicit in the manifesto, some of the organizers thought a natural next step would be to collaboratively develop a roadmap of the movement, which could serve as a compass to guide action.

In november 2016 some ideas had emerged that were later polished by some GOSHers in a writing workshop at CERN, in order to prepare a document to discuss with the hundred participants of GOSH 2017. The session in Chile was facilitated by Max Liboiron, and gathered input of all participants in terms of defining strategies, priorities, goals of the community.

All this information was curated during seven months of online meetings and writing sessions, plus one more meeting at CERN in 2017 to finalize the writing and publication of the official document, in January 2018.

The final roadmap is structured in three main sections: LEARN, SUPPORT and GROW, with the goal of making open science hardware ubiquitous by 2025. It was presented at various meetings, conferences and workshops around the world.

❝❞

“The writing process involved so many people at different times that it felt very collaborative. Although it was exhausting to understand how to organize [the contributions], or who had the last word on each topic, it finally ended up being very representative”

Scaling hardware, growing community

With the aim of growing the community, the next natural step was to hold the global gathering 2018 in Asia. After evaluating different options considering community feedback, OpenFiesta, an institute at Tsinghua University in Shenzhen (China) was chosen for the event. Following the same principle since the beginning, the hundred attendees of the event did not have to pay for travelling or for participating.

The first three days of the meeting were each dedicated to a section of the roadmap, with unconference sessions, workshops and project showcasing. The last day was reserved to a group session where everyone picked up and self-assigned concrete actions derived from the roadmap strategy to push further, which were documented in GitLab. A volunteer team was again responsible for documenting all sessions and activities online, plus managing audiovisual material.

The public event was organized in X-Factory - a public-private space for prototyping and batch production - where community projects were presented and an art-science exhibition was held. Almost a tradition, pre and post gathering some GOSHers dedicated time to collaborative work and to visit emblematic local spaces such as the Huaqiangbei hardware market.

❝❞

We find maker sprit everywhere and it's quite easy to develop something and have a startup in China. But here [with GOSH] there is an opportunity, anyone can use these open source devices that contribute to science and to good.

David Li (Shenzhen Open Innovation Lab), Fernán Federici Noe (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile), Francois Grey (University of Geneva and CERN), Greg Austic (Our Sci), Jenny Molloy (University of Cambridge), Ji Li (Open FIESTA, Tsinghua University), Julieta Arancio (CENIT-CONICET), Marc Dusseiller (Hackteria), Shannon Dosemagen (Public Lab), Vicky Xie (Shenzhen Open Innovation Lab)

Distributed movement

During GOSH 2018 some organizers announced that there would not be a global event in 2019. The volume of volunteer work exceeded the capabilities of the small organizing team, and the growth of the community makes it difficult to gather everyone in one global event. After three years of global meetings and growing community, organizers decided to step back and propose some reflection on how to move forward more efficiently, so the strategy defined in the roadmap becomes real.

❝❞

We got to the point where we have to exclude people from coming to the meeting, half people couldn’t come to this GOSH [2018], which is not the position we’d like to be in.

One of the proposals that emerged was to hold regional, decentralized meetings that keep the GOSH spirit alive and consolidate regional and local communities.

The first case of decentralization was AfricaOSH after GOSH 2017. In Chile, Thomas Mboa (Mboa Lab, Cameroon) and Jorge Appiah (Kumasi Hive, Ghana) met and decided to run a GOSH version for the African community, already in its third edition.

In Latin America, some GOSHers were already working together around a students’ event of free/libre technologies for development, TecnoX. After GOSH2018 they secured funds until 2022 to promote a regional open science hardware network, which operates through a methodology of “GOSH residences” in different Latin American countries. In the residences participants spend three weeks replicating open science hardware designs with local materials. The first edition in Porto Alegre was a success, and will be replicated in Peru in 2020 under the theme of ‘health technologies’.

❝❞

I would really like to see more projects, people working concretely on a project together, something that you haven't done before.

In Toronto, Canada, the first Great Lakes GOSH was held in 2019 with the aim of fostering collaboration and identifying ways to support participants and collaborate more effectively. The documentation of the three meeting days plus post hackathon can be found in the GOSH forum.

In Switzerland, GOSHers Europe met to organize a crowdfunding campaign to support work on the ReSeq project, or reuse of an old DNA sequencer to turn it into an open science hardware instrument. The campaign was a success and the work is currently in development.

More recently, 2020 has already brought news: some GOSHers participated in the creation of an open hardware mentorship program, with the aim of providing support for open hardware projects in terms of best practices and connection to communities in similar fields. The first cohort is ongoing, featuring many open hardware projects for science.

Also in February, the University of Bath Open Source Hardware Group organized a 3-day workshop where participants explored the challenges faced when making open hardware in academic contexts and explored collaborations to address them.

Epilogue

There’s a lot going on around open science hardware. More and more people join and see its benefits for research, education and environmental justice. Some universities are starting to see its benefits, policy recommendations appear in some publications, and even the European Union commission is discussing the topic.

What is the role of GOSHers in this scenario? Which governance structure is needed to gain momentum and push for change? Is there a need for one? Opinions are as diverse as GOSHers...

❝❞

[mass difference and moving together] mean a lot of solidarity work: I don’t understand you, I can’t deal with your accent and I can’t understand what you’re saying but I will believe that we’re working towards the same goal, which doesn’t necessarily mean that we agree.